Although the tone of the Chancellor was very upbeat, the reality of the budget was clearly “steady as we go” against the backdrop of financial market jitters, the continuing conflict in Ukraine and a looming election. Critic or supporter – perhaps that very much depends on the extent to which the (lengthy) budget represents a return to sensible policy?

The majority of the key tax-raising measures announced by the Chancellor in his Autumn Statement also take effect from April 2023. The main revenue raising strategy is to freeze various tax allowances, including the Income Tax Personal Allowance and the VAT threshold. With inflation climbing to over 10%, the government receives its own windfall in terms of VAT receipts. The decision to reduce the additional (upper) rate threshold next year means that more taxpayers will pay tax at the 45% rate, thus spreading some of the tax burden, as anticipated, to higher earners.

Looking at the position of the ‘private client’ there is some bad news in the form of a reduction in the tax-free allowances for both Dividend Tax and Capital Gains Tax (CGT) over the next two years. The Chancellor has also extended the scope of a windfall tax on the energy sector. There are always winners and losers, and online businesses might breathe a sigh of relief that the government has decided not to introduce an online sales tax. Meanwhile, reforming measures for business rates continue to evolve, with a new form of small business rate relief planned to protect certain businesses from the large increase to bills that may well occur thanks to the update in rateable values of all non-domestic properties in England to reflect their value as at 1 April 2021.

Combined with the many mini-budgets and statements made towards the end of 2022, this Budget brings change; good, bad, and often to be determined with time. What is clear is that 2023 remains a year of opportunity and we are here to work alongside you and help you grow

What about the cost of living?

Energy Costs

The Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) brings a typical household energy bill in Great Britain down to around £2,500 per year. It has now been announced that the £2,500 EPG will be extended by 3 months to 30th June 2023, before increasing to £3,000 until the end of the EPG period on 31 March 2024. This extra 3 months at £2,500 will be worth £160 for a typical household.

A new scheme for businesses, charities and the public sector has been confirmed. The Business Energy Bills Discount Scheme will run until 31 March 2024, giving non-domestic customers discounts on their gas and electricity bills.

Childcare

Additional support is being provided towards childcare costs in what the government describes as a ‘childcare revolution’. This includes 30 hours of free childcare for every child over the age of 9 months, with support being phased in until every eligible working parent of under 5s gets this support by September 2025.

For Universal Credit claimants, the government will also pay childcare costs in advance rather than arrears, when parents move into work or increase their hours. The maximum they can claim will also be boosted to £951 for one child and £1,630 for two children, an increase of around 50%.

Benefits and State Pension

As confirmed at Autumn Statement 2022, the government will also increase benefits, including the State Pension, paid to recipients in the tax year to 5 April 2024, by 10.1%.

This increase in the State Pension means that most pensioners will receive £10,600 in 2023/24, where they have 35 qualifying years. We urge you again to check your contribution record on your Government Gateway account and consider making Class 3 voluntary National Insurance (NI) contributions in respect of missing qualifying years. Normally it is only possible to make voluntary NI contributions for the past 6 tax years, but until 31 July 2023, it is possible to go back as far as 6 April 2006 and pay additional contributions at the 2022/23 Class 3 rate of £15.85 per week.

In-year Class 3 contributions for 2023/24 will increase to £17.45 per week.

Duties on fuel frozen

The proposed 11p rise in fuel duty will be cancelled thus maintaining last year’s 5p cut for another 12-months.

Draught Relief

Draught Relief has also been significantly extended from 5% to 9.2%, so that the duty on an average draught pint of beer served in a pub, from 1 August 2023, will be up to 11 pence lower than the duty in supermarkets. The commitment to duty on a pub pint being lower than the supermarket has been termed the “Brexit Pubs Guarantee” by the Chancellor, and this change will also be enjoyed by every pub in Northern Ireland thanks to the Windsor Framework.

What about income tax?

It’s not so much that taxes are increasing but rather than more is being taxed

Increasing Liabilities

The personal allowance and basic rate band threshold are now frozen in place until 5 April 2028. As earnings increase, individuals will move into higher tax bands. This is often referred to as ‘fiscal drag’ because it will raise more tax without the government increasing income tax rates.

The personal allowance continues to be partially and then fully withdrawn for higher earners, with £1 of personal allowance lost for every £2 of adjusted net income over £100,000.

Other Allowances

Savings income continues to benefit from a personal savings allowance of £1,000 for basic rate taxpayers and £500 for higher rate taxpayers. Dividend income attracts a £1,000 dividend allowance in 2023/24, down from the £2,000 allowance seen in previous years. These allowances are in addition to the personal allowance and attract a 0% rate of income tax.

For those living in Scotland and classed as Scottish taxpayers have a slightly different banding system for ‘other income’ (non-savings, non-dividend) as follows:

The application of income tax to savings and dividends income is the same as for the rest of the UK.

Pension Tax Relief

There was good news in the Budget for those saving in a personal pension. The current pension lifetime allowance (LTA) charge is being abolished from 6 April 2023, although the actual change to the Lifetime allowance doesn’t take effect until April 2024.

Individuals may be able to receive 25% of their pension savings as a tax-free lump sum when they become entitled to their pension benefits. This is currently capped at 25% of the LTA and going forwards, for most individuals, will remain capped at £268,275, despite the planned change in the level of the Lifetime Allowance.

The pension Annual Allowance (AA) increases from £40,000 to £60,000 from 6 April 2023. The AA applies to the combined pension input by the individual and, in the case of employees, their employer. Pension contributions in excess of the AA result in a tax charge on the individual, although they may take advantage of unused AA amounts from the 3 previous tax years.

For those with high incomes, the AA is tapered. From 6 April 2023, where a taxpayer’s adjusted income exceeds £260,000 (increasing from £240,000), the AA is tapered by £1 for every £2 in excess of £260,000, down to a minimum of £10,000 (increasing from £4,000).

The Money Purchase Annual Allowance (MPAA) replaces the AA when an individual starts to flexibly access a defined contribution pension scheme. The MPAA will increase from £4,000 to £10,000 on 6 April 2023.

Tax Efficient Savings

There were no changes to the annual limits for Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs), Child Trust Funds or the Junior ISA. These limits remain at £20,000, £9,000 and £9,000 respectively.

What about other taxes?

Capital Gains Tax

In the Autumn Statement, the Chancellor announced that the £12,300 annual tax-free capital gains tax exemption (or allowance) will be reduced to just £6,000 in 2023/24 and only £3,000 in 2024/25.

This change will mean that those disposing of capital assets will pay more tax, where the new lower allowance is exceeded.

Couples who are in the process of separating, or who have commenced divorce proceedings, need to be aware of new rules taking effect from 6 April 2023 concerning the transfer of capital assets between them as a result of their separation.

If you are planning any capital disposals, please contact us to discuss the best strategy for the disposal.

Inheritance Tax

In the 2023 Autumn Statement, the inheritance tax nil rate band was frozen at £325,000 until April 2028. The residence nil rate band will also remain at £175,000 and the residence nil rate band taper will continue to start at £2 million.

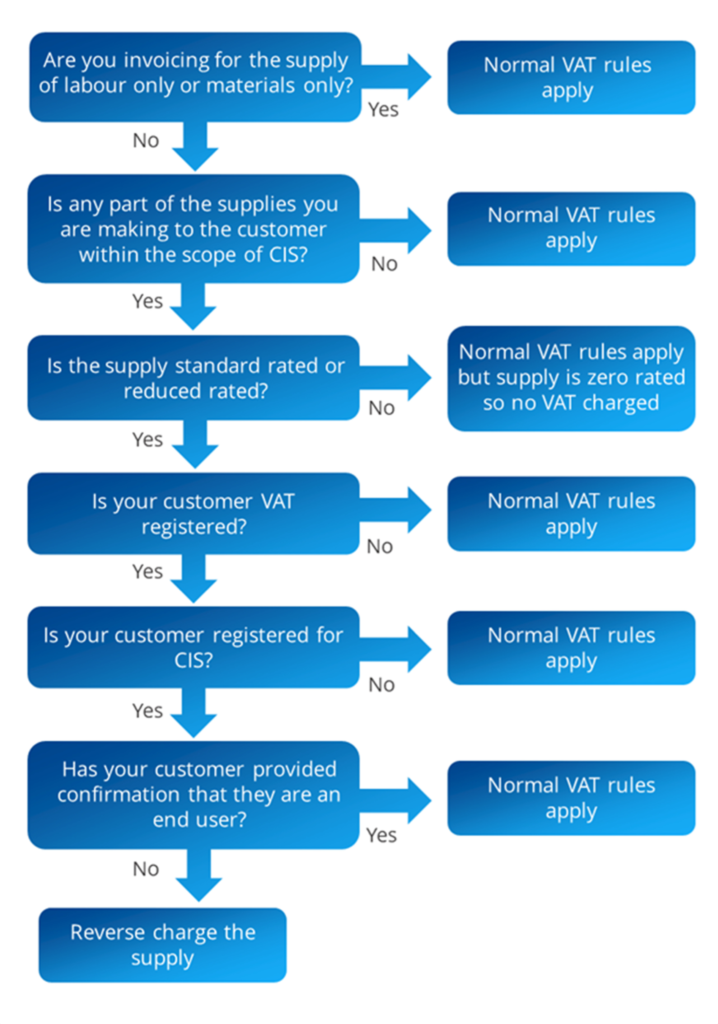

VAT

The VAT registration and deregistration thresholds continue to be frozen at £85,000 and £83,000 respectively, instead of increasing each year in line with inflation. This will remain the case until March 2026.

Since 1 January 2023, a new penalty regime has been in operation for late VAT return submission and late payment of VAT. The new system is designed to target more persistent offenders, with penalties escalating quickly where defaults reoccur.

Business Taxes

National Insurance Contributions (NIC) for the self-employed in 2023/24

Self-employed individuals are required to pay Class 2 and Class 4 NICs if their profits exceed £12,570. These NICs are usually collected with the individual’s income tax self-assessment payments.

For 2023/24, Class 2 NICs are calculated at £3.45 per week and Class 4 NICs are calculated at 9% on profits between £12,570 and £50,750, and at 2% on profits over £50,750.

Tax Relief for expenditure on plant and machinery

The Annual Investment Allowance (AIA), giving 100% tax relief to unincorporated businesses and companies investing in qualifying plant and machinery, is now permanently set at £1million.

The super-deduction, which gives enhanced 130% relief for new qualifying plant and machinery acquired by companies, will end on 31 March 2023.

As a replacement for the super-deduction, ‘full expensing’ (effectively 100% tax relief, called a ‘First Year Allowance’ (FYA)) will be available to companies (not unincorporated businesses) incurring expenditure on new qualifying plant and machinery between 1 April 2023 and 31 March 2026. The qualifying criteria is quite broad although there are exclusions, including cars and features integral to a building (for example, heating systems). With regard to ‘integral features’, a smaller 50% FYA will be available. Subsequent disposals of assets on which one of these FYAs has been claimed will trigger a clawback of tax relief at a rate of 100% or 50% of the disposal proceeds, depending on the rate of the original relief. These new FYAs will mainly be of interest to companies that have already fully utilised their £1million AIA.

The separate 100% FYA for electric vehicle charge points remains available for unincorporated businesses and companies until Spring 2025.

This announcement will have very little impact on the majority of businesses and it should be remembered that these allowances do not increase the tax relief available but simply accelerates it – this is more about cashflow planning.

Corporate Taxes

New rates from 1 April 2023

From 1 April 2023, the rate of Corporation Tax will increase to 25% if a company’s profits exceed £250,000 a year. The current 19% rate will however continue to apply where profits are no more than £50,000 a year.

Where a company’s profits fall between £50,000 and £250,000 a year, the profits are taxed at the higher 25% rate, but a ‘marginal relief’ is given to reduce the liability, with the effective rate being closer to 19% for those with profits just over £50,000.

Companies in the same corporate group (or otherwise connected by association) must share the £50,000 and £250,000 thresholds between them, making the 25% rate more likely to apply. We will discuss the implication of associated companies in a future newsletter.

Research & Development (R&D) Reliefs

From 1 April 2023 a raft of changes is coming to the R&D tax relief regime and claimant companies should consider obtaining updated advice if they’ve not already done so. The key changes are:

- For SME companies, R&D tax relief rates will be reduced from 230% to 186%.

- For loss-making SME companies, the current payable credit of 14.5% will only be available for companies whose R&D expenditure constitutes at least 40% of their total expenditure. For R&D claimants that don’t meet the new 40% test, the payable credit will be reduced from 14.5% to 10% of the eligible loss.

- Qualifying R&D expenditure will be expanded to include data licences and cloud computing services.

- New claimants (those who have not made a claim in the previous 3 years) will be required to inform HMRC of their intention to make a R&D claim within 6 months of the end of the accounting period to which the claim relates.

From 1 August 2023, additional information requirements will need to be fulfilled when making a R&D claim.

A £500 million per year package of support for 20,000 research and development (R&D) intensive businesses through changes to R&D tax credits was announced. In full, the Chancellor’s announced changes in this important area are:

- The scheme is targeted specifically at loss making R&D intensive SMEs. Focusing support towards those most impacted by the rate changes introduced at Autumn Statement 2022.

- A company is considered R&D intensive where its qualifying R&D expenditure is worth 40% or more of its total expenditure.

- Eligible loss-making companies will be able to claim £27 from HMRC for every £100 of R&D investment, instead of £18.60 for non-R&D intensive loss makers.

- Around 1,000 claiming companies will come from the pharmaceutical and life sciences industry. This will support the development of life saving medicines.

- Around 4,000 digital SMEs will be from the computer programming, consultancy, and related activities sector. This will support the development of AI, machine learning and other digital based technologies.

- Around 3,000 other manufacturing firms, and another 3,000 professional, scientific, and technical activities firms will also qualify for the enhanced support.

- This builds on previously announced changes to support modern research methods by expanding the scope of qualifying expenditure for R&D reliefs to include data & cloud computing costs.

The permanent increase from 13% to 20% for the R&D Expenditure Credit rate announced at Autumn Statement 2022 also means the UK now has the joint highest uncapped headline rate of tax relief in the G7 for large companies

Creative industries tax reliefs

The government continues to support the creative industries by reforming and enhancing film, TV and video games tax reliefs. The government will also extend the temporary higher rates of theatre, orchestra, and museums and galleries tax reliefs for 2 further years until April 2025.

Employment Taxes

- National Insurance Contributions (NICs)

Like the main income tax bandings, employer and employee NIC thresholds are now also frozen until 5 April 2028. This broadly means that employers’ NIC will continue to apply at 13.8% to earnings in excess of £9,100 a year (£175 per week) and employees will continue to pay 12% on earnings between £12,570 and £50,270 and 2% thereafter.

- Company Cars and Other Benefits

Employees are required to pay income tax on certain non-cash benefits. For example, the provision of a company car constitutes a taxable ‘benefit in kind’. Employers also pay Class 1A NIC at 13.8% on the value of benefits.

The set percentages used to calculate company car benefits are fixed until 5 April 2025 before slight increases apply to most car types, including electronic and ultra-low emission, from 6 April 2025.

More imminently, the figures used to calculate benefits-in-kind on employer-provided vans, van fuel (for private journeys in company vans), and car fuel (for private journeys in company cars) will increase in line with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) from 6 April 2023. These will become:

- Van benefit £3,960

- Van fuel benefit £757

- Car fuel benefit multiplier £27,800

Investment Zones

The Government will establish 12 ‘Investment Zones’ across the UK, including a promise to have at least one each in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales.

Each successful zone will have access to £80m funding over 5 years and benefit from a package of tax reliefs. These include relief from Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT), enhanced capital allowances for plant and machinery, enhanced structures and buildings allowances and relief from secondary Class 1 National Insurance Contributions (NICs) for qualifying employers on the earnings of eligible employees up to £25,000 per annum.

Venture Capital Schemes

The Government is increasing the generosity and availability of the Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme for start-up companies. The amount of investment that companies will be able to raise under the scheme will increase from £150,000 to £250,000. The gross asset limit will be increased from £200,000 to £350,000 and the investment must be made within 3 years (increased from 2 years) of trade commencing. In a bid to support these changes, the annual investor limit will be doubled to £200,000. The changes take effect from 6th April 2023.

Simplifying the tax system

Changes to simplify the tax system of the UK were underlined by a number of changes to positively impact the lives of small business owners. They are:

- Changes to the Enterprise Management Incentives (EMI) scheme from April 2023 to simplify the process to grant options and reduce the administrative burden on participating companies. This includes, from 6 April 2023, removing requirements to sign a working time declaration and setting out details of share restrictions in option agreements.

- Delivery of IT systems to enable tax agents to payroll benefits in kind on behalf of their clients – allowing agents to better support their clients and reducing burdens on employers.

- The government will extend the Help to Save scheme by 18-months, on its current terms, until April 2025. A consultation will also be launched on longer terms options for the scheme.

- Measures to simplify the customs import and export processes, including improvements to the Simplified Customs Declaration Process, and the Modernising Authorisations project.